A sermon for 15th September 2024 (Trinity 16 B – proper 19)

Isaiah 50.4–9a, James 3.1–12, Mark 8.27–38

I haven’t posted a sermon for ages, as I don’t usually write them out in full, but here goes.

‘Who do people say that I am?’ Jesus asks.

He knows that people have strong views about him – by this point in Mark’s Gospel he has been adored, admired and believed, but also criticized, doubted, misunderstood, even threatened. The disciples aren’t sure how to answer Jesus’ question because the answer would depend very much on who you ask!

Maybe because they’re his friends, they don’t remind him that he’s been called him a lawbreaker or that some people think he’s possessed, but stick to the more positive things they’ve heard: that Jesus might be John the Baptist or Elijah or another of the prophets come back from the dead. These aren’t unreasonable suggestions. Jesus speaks and acts powerfully: so far in Mark’s Gospel he’s controlled the weather, healed people, miraculously fed a crowd of several thousand, and challenged those in authority. He absolutely comes across as a prophet.

‘And who do you say that I am?’ Jesus then asks. Peter is the one who dares to speak. ‘You are the Messiah,’ he says. Not just a prophet but more than that, the one who is anointed by God, in whom there is hope for salvation, specifically freedom from oppression.

So, Peter is kind of right.

He has the right word, but hasn’t fully understood what it means, and it’s likely that others won’t either, so Jesus sort of sets that word aside in order to explain more.

Perhaps Peter should have remembered the words from Isaiah. The figure that Isaiah identifies as ‘the servant of God’ declares ‘I gave my back to those who struck me and my cheeks to those who pulled out the beard; I did not hide my face from insult and spitting’. If those words sound familiar it may be because (in a slightly different translation) they are used in Handel’s great Oratorio, The Messiah. Today’s passage from Isaiah connects prophetic speaking with a willingness to endure suffering – a connection which all the old testament prophets would have recognised in their own experience, and which Jesus also sees as intrinsic to his vocation: And so he begins to teach them that he must undergo great suffering, and be rejected.

Peter could simply have turned the question round and asked Jesus, ‘well, who do you say that you are?’ But Jesus beats him to it, describing himself as Son of Man – on one level this is just ‘ben adam’ as in ‘human being’ or ‘a mere human being’ – that is, someone who is vulnerable to suffering. But it also echoes the apocalyptic vision in the book of Daniel in which the Son of Man embodies the salvation and glory of God’s people no longer suffering but vindicated. Jesus as Son of Man makes perfect sense in today’s gospel because he’s talking about both his coming suffering, and the glory of the resurrection.

So there is a lot going on behind Jesus’ original questions. They’re not trick questions but they are complex and multi-layered, so it’s not surprising that Peter misses the mark, or that the rest of the disciples don’t even feel confident answering at all! It feels like Jesus is bringing together a lot of important ideas that won’t truly make sense even to his closest followers until the whole story has unfolded.

What they need right now is to understand what it all means for them as disciples. Let’s start with Peter, and who he is.

In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus calls Peter as a disciple, drawing attention to his name, which means ‘rock’ to commend his faith. ‘On this rock I will build my Church’ he says. By contrast, today when Peter questions Jesus’ coming suffering, he is given a rather more disturbing name: ‘Get behind me, Satan’ Jesus says. Seems a little harsh, right?.

We met actual Satan earlier in the gospels when Jesus is tempted by him while fasting for forty days in the wilderness. Matthew and Luke both provide more detail than Mark does, outlining three temptations, of which two are particularly relevant: Satan tries to get the very hungry Jesus to turn stones into bread, then tells Jesus that if he jumps off the top of the Temple it’ll prove that God won’t let him get hurt – Satan quotes Psalm 91, ‘his angels will bear you up, lest you dash your foot against a stone’. Jesus resists all three temptations and Satan gives up – for the time being.

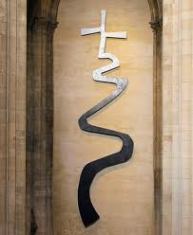

Notice that two of the temptations mention stones, and remember that Peter has been named by Jesus as ‘the rock’. This is a really key material image in scripture, with a lot of meanings attached to stones. I don’t think it’s a huge stretch here to suggest that when Peter the rock tells Jesus that he shouldn’t suffer, Jesus realises it’s the same temptation again and it’s as if Satan is back for another go. No wonder he reacts so harshly. Jesus resisted that temptation before and he does so again now. He’ll have to resist the same temptation in Gethsemane and on the cross.

So who is Peter in this whole incident? He is the rock, the one with the courage the speak and the insight to name Jesus as Messiah. But he’s also potentially a stumbling block, a temptation, someone whose words seeks to pull Jesus away from his vocation and purpose. Fortunately through the grace of God stumbling blocks can be repositioned to become the most amazing cornerstones. That’s what Jesus seeks to do: he is turning Peter from a dangerous temptation into someone who can grasp not just Jesus’ coming suffering but also his own.

Jesus rebukes Peter in front of all the disciples not to shame him, but because all he did is put into words what the others were probably thinking, and what many of us might be thinking too: this misunderstanding and mis-speaking isn’t a Peter thing, it’s an everyone thing, and we all need to hear the next bit of what Jesus has to say.

Which is where we move from asking ‘who is Jesus’ and ‘who is Peter’ to the question of ‘so who are we?’

We may be, at times, people who wish that faith protects people from the thorns about our path or from life’s storms. As one of my favourite hymns points out, it is not that the journey is objectively easier if we have faith, it’s that we’re not alone in it: ‘be our strength in hours of weakness, in our wanderings be our guide, through endeavour, failure, danger, Father be thou at our side’.

Who are we? We are people with someone to follow, someone who in his incarnation embraced the inevitability of suffering that comes with living a human life, as well as embracing the necessity of suffering in the story of salvation; a Saviour who stilled the storm not from the safety of the shore but in the company of his friends, from a flimsy, sinking boat.

We may be, at times, people who are tempted to deny or downplay the costliness of discipleship, of the life of faith. We may be in denial in a global context about the ongoing threat of death or serious harm that faith can bring, or about the much lower level friction we may experience when we try to live faithfully in a complex world, or the emotional pain of trying to reconcile human suffering with what we believe about the love of God. We may sometimes be people who are (as he puts it) ashamed of Jesus and his teaching, especially when it difficult, or when we don’t feel equipped to express our faith in a way that will make sense to people. In the light of today’s reading from the letter of James, which is all about the power of speech and how we spend that power, it’s worth noting that Peter’s mistake is only in words, and yet Jesus recognises its potential for great harm.

I don’t know if you’ve heard the saying about budgeting, that if you look after the pennies, the pounds will look after themselves? For most of us in this context the cost of discipleship is counted in pennies, but they still add up. Our words or lack of words, especially on behalf of those for whom the cost is counted in pounds – these express and shape who we are. So who are we?

We are fallible: we are people who sometimes – often – misunderstand and mis-speak, who fail to realise the power of what we say and that our words can undermine the vocation of others, or downplay the crosses that others bear – we are all of us capable of being stumbling blocks.

We are also called by God, to follow Jesus, to discern what is the particular cross that we must pick up, and then walk the difficult path before us alongside one another with Christ as our guide.

We are works in progress: we are people with questions, for whom the most important answers are rarely fully understood in theory or captured in propositional statements, but are worked out over the course of a life’s journey, and often during the times when we find that journey most challenging.

Who are we? In the end, it is less about who we are, and more about whose we are. Knowing that we are made and named by God, we will know who we are most truly when we grasp who God believes us to be. This was Peter’s journey, and it can be our journey too.